Art Gems for the Home and Fireside 1890 Antique Book Mrs Charles Walter Stetson Plain Grey Cover

| Charlotte Perkins Gilman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Built-in | (1860-07-03)July 3, 1860 Hartford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | Baronial 17, 1935(1935-08-17) (aged 75) Pasadena, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Notable works | "The Yellow Wallpaper" Herland Women and Economics |

| Signature | |

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (; née Perkins; July iii, 1860 – Baronial 17, 1935), also known by her get-go married name Charlotte Perkins Stetson, was an American humanist, novelist, author, lecturer, advocate for social reform, white supremacist, and eugenicist.[1] She was a utopian feminist and served as a role model for futurity generations of feminists because of her unorthodox concepts and lifestyle. She has been inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[ii] Her best remembered work today is her semi-autobiographical brusk story "The Yellow Wallpaper", which she wrote after a severe bout of postpartum psychosis.

Early on life [edit]

Gilman was born on July 3, 1860, in Hartford, Connecticut, to Mary Perkins (formerly Mary Fitch Westcott) and Frederic Beecher Perkins. She had but one blood brother, Thomas Adie, who was fourteen months older, because a physician brash Mary Perkins that she might die if she bore other children. During Charlotte's infancy, her father moved out and abased his wife and children, and the remainder of her babyhood was spent in poverty.[one]

Since their mother was unable to back up the family unit on her own, the Perkinses were often in the presence of her father's aunts, namely Isabella Beecher Hooker, a suffragist; Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin; and Catharine Beecher, educationalist.

Her schooling was erratic: she attended seven unlike schools, for a cumulative full of just four years, ending when she was fifteen. Her mother was non appreciating with her children. To keep them from getting injure every bit she had been, she forbade her children from making strong friendships or reading fiction. In her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Gilman wrote that her mother showed affection only when she thought her young daughter was asleep.[3] Although she lived a childhood of isolated, impoverished loneliness, she unknowingly prepared herself for the life that lay ahead by frequently visiting the public library and studying ancient civilizations on her own. Additionally, her father's love for literature influenced her, and years later he contacted her with a listing of books he felt would be worthwhile for her to read.[4]

Much of Gilman'south youth was spent in Providence, Rhode Isle. What friends she had were mainly male, and she was unashamed, for her fourth dimension, to call herself a "tomboy".[5]

Her natural intelligence and breadth of knowledge always impressed her teachers, who were nonetheless disappointed in her because she was a poor student.[6] Her favorite subject was "natural philosophy", especially what later would become known as physics. In 1878, the eighteen-year-sometime enrolled in classes at the Rhode Island School of Design with the monetary help of her absent father,[7] and subsequently supported herself as an artist of merchandise cards. She was a tutor, and encouraged others to expand their artistic creativity.[viii] She was also a painter.

During her time at the Rhode Island Schoolhouse of Design, Gilman met Martha Luther in about 1879[9] and was believed to exist in a romantic relationship with Luther. Gilman described the shut relationship she had with Luther in her autobiography:

We were closely together, increasingly happy together, for 4 of those long years of girlhood. She was nearer and dearer than any i upward to that fourth dimension. This was love, merely not sex... With Martha I knew perfect happiness... We were non only extremely addicted of each other, simply we had fun together, deliciously...

—Charlotte P. Gilman, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1935)

Messages between the ii women chronicles their lives from 1883 to 1889 and contains over 50 letters, including correspondence, illustrations and manuscripts.[10] They pursued their relationship until Luther chosen it off in club to marry a man in 1881. Gilman was devastated and detested romance and dearest until she met her first married man.[9]

Machismo [edit]

In 1884, she married the artist Charles Walter Stetson, after initially declining his proposal because a gut feeling told her it was not the right thing for her.[11] Their only child, Katharine Beecher Stetson, was born the post-obit year on March 23, 1885. Charlotte Perkins Gilman suffered a very serious bout of postal service-partum low. This was an age in which women were seen as "hysterical" and "nervous" beings; thus, when a woman claimed to be seriously sick subsequently giving birth, her claims were sometimes dismissed.[12]

Gilman moved to Southern California with her girl Katherine and lived with friend Grace Ellery Channing. In 1888, Charlotte separated from her husband – a rare occurrence in the late nineteenth century. They officially divorced in 1894. Afterwards their divorce, Stetson married Channing.[xiii] [14] During the year she left her husband, Charlotte met Adeline Knapp, chosen "Delle". Cynthia J. Davis describes how the two women had a serious human relationship. She writes that Gilman "believed that in Delle she had institute a manner to combine loving and living, and that with a woman as life mate she might more easily uphold that combination than she would in a conventional heterosexual marriage." The relationship ultimately came to an end.[15] [xvi] Post-obit the separation from her hubby, Charlotte moved with her daughter to Pasadena, California, where she became active in several feminist and reformist organizations such every bit the Pacific Coast Women's Printing Clan, the Woman'southward Brotherhood, the Economic Club, the Ebell Society (named after Adrian John Ebell), the Parents Association, and the State Council of Women, in addition to writing and editing the Bulletin, a journal put out by one of the earlier-mentioned organizations.[17]

In 1894, Gilman sent her daughter due east to live with her onetime hubby and his second married woman, her friend Grace Ellery Channing. Gilman reported in her memoir that she was happy for the couple, since Katharine's "second mother was fully as good every bit the showtime, [and perhaps] better in some ways."[18] Gilman also held progressive views about paternal rights and acknowledged that her ex-married man "had a right to some of [Katharine's] gild" and that Katharine "had a correct to know and love her male parent."[xix]

Afterward her mother died in 1893, Gilman decided to move back east for the offset time in 8 years. She contacted Houghton Gilman, her offset cousin, whom she had non seen in roughly fifteen years, who was a Wall Street attorney. They began spending a meaning amount of time together almost immediately and became romantically involved. While she would go along lecture tours, Houghton and Charlotte would substitution letters and spend as much time as they could together before she left. In her diaries, she describes him every bit being "pleasurable" and it is clear that she was deeply interested in him.[xx] From their hymeneals in 1900 until 1922, they lived in New York City. Their spousal relationship was nada similar her commencement one. In 1922, Gilman moved from New York to Houghton's old homestead in Norwich, Connecticut. Following Houghton'southward sudden death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1934, Gilman moved back to Pasadena, California, where her daughter lived.[21]

In Jan 1932, Gilman was diagnosed with incurable breast cancer.[22] An abet of euthanasia for the terminally ill, Gilman died past suicide on Baronial 17, 1935, by taking an overdose of chloroform. In both her autobiography and suicide notation, she wrote that she "chose chloroform over cancer" and she died apace and quietly.[21]

Career [edit]

At one point, Gilman supported herself by selling soap door to door. After moving to Pasadena, Gilman became active in organizing social reform movements. As a delegate, she represented California in 1896 at both the National American Woman Suffrage Clan convention in Washington, D.C., and the International Socialist and Labor Congress in London.[23] In 1890, she was introduced to Nationalist Clubs movement which worked to "stop capitalism's greed and distinctions between classes while promoting a peaceful, ethical, and truly progressive homo race." Published in the Nationalist mag, her poem "Like Cases" was a satirical review of people who resisted social change, and she received positive feedback from critics for it. Throughout that same twelvemonth, 1890, she became inspired plenty to write 15 essays, poems, a novella, and the short story The Yellowish Wallpaper. Her career was launched when she began lecturing on Nationalism and gained the public'due south eye with her start volume of verse, In This Our Earth, published in 1893.[24] As a successful lecturer who relied on giving speeches as a source of income, her fame grew along with her social circle of similar-minded activists and writers of the feminist movement.

"The Yellow Wallpaper" [edit]

The Yellow Wallpaper, 1 of Gilman's most popular works, originally published in 1892, before her marriage to George Houghton Gilman.

In 1890, Gilman wrote her short story "The Yellow Wallpaper",[25] which is now the all-time best selling volume of the Feminist Press.[26] She wrote information technology on June 6 and seven, 1890, in her habitation of Pasadena, and information technology was printed a year and a one-half later in the January 1892 issue of The New England Magazine.[1] Since its original printing, it has been anthologized in numerous collections of women's literature, American literature, and textbooks,[27] though non ever in its original form. For instance, many textbooks omit the phrase "in matrimony" from a very important line in the showtime of story: "John laughs at me, of grade, but one expects that in marriage." The reason for this omission is a mystery, as Gilman's views on marriage are made clear throughout the story.

The story is virtually a adult female who suffers from mental illness after three months of being closeted in a room past her husband for the sake of her health. She becomes obsessed with the room's revolting xanthous wallpaper. Gilman wrote this story to change people's minds about the role of women in order, illustrating how women's lack of autonomy is detrimental to their mental, emotional, and even physical wellbeing. This story was inspired by her treatment from her showtime husband.[28] The narrator in the story must practise as her husband (who is also her doctor) demands, although the handling he prescribes contrasts directly with what she truly needs—mental stimulation and the freedom to escape the monotony of the room to which she is bars. "The Yellow Wallpaper" was essentially a response to the doctor (Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell) who had tried to cure her of her depression through a "remainder cure". She sent him a re-create of the story.[29]

Other notable works [edit]

Gilman's first volume was Art Gems for the Dwelling house and Fireside (1888); however, information technology was her showtime book of poetry, In This Our Earth (1893), a collection of satirical poems, that first brought her recognition. During the next two decades she gained much of her fame with lectures on women'due south issues, ethics, labor, human being rights, and social reform.[ane] Her lecture tours took her across the United States.[i] She oft referred to these themes in her fiction.[21]

In 1894–95 Gilman served equally editor of the magazine The Print, a literary weekly that was published past the Pacific Coast Women'due south Press Association (formerly the Bulletin). For the twenty weeks the magazine was printed, she was consumed in the satisfying achievement of contributing its poems, editorials, and other articles. The short-lived paper's printing came to an terminate as a issue of a social bias confronting her lifestyle which included existence an unconventional mother and a woman who had divorced a human.[30] Subsequently a iv-month-long lecture tour that ended in Apr 1897, Gilman began to think more deeply well-nigh sexual relationships and economics in American life, eventually completing the starting time draft of Women and Economic science (1898). This book discussed the part of women in the dwelling, arguing for changes in the practices of child-raising and housekeeping to alleviate pressures from women and potentially allow them to expand their work to the public sphere.[31] The book was published in the post-obit year and propelled Gilman into the international spotlight.[32] In 1903, she addressed the International Congress of Women in Berlin. The next year, she toured in England, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

In 1903 she wrote 1 of her most critically acclaimed books, The Home: Its Work and Influence, which expanded upon Women and Economics, proposing that women are oppressed in their home and that the environment in which they alive needs to exist modified in club to be good for you for their mental states. In between traveling and writing, her career as a literary figure was secured.[33] From 1909 to 1916 Gilman single-handedly wrote and edited her own magazine, The Precursor, in which much of her fiction appeared. By presenting material in her mag that would "stimulate thought", "agitate promise, courage and impatience", and "limited ideas which demand a special medium", she aimed to go against the mainstream media which was overly sensational.[34] Over seven years and two months the magazine produced fourscore-six issues, each twenty 8 pages long. The magazine had nearly ane,500 subscribers and featured such serialized works as "What Diantha Did" (1910), The Crux (1911), Moving the Mount (1911), and Herland. The Forerunner has been cited equally being "perhaps the greatest literary achievement of her long career".[35] Afterward its 7 years, she wrote hundreds of articles that were submitted to the Louisville Herald, The Baltimore Sun, and the Buffalo Evening News. Her autobiography, The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which she began to write in 1925, appeared posthumously in 1935.[36]

Balance cure treatment [edit]

Perkins-Gilman married Charles Stetson in 1884, and less than a year later gave nascence to their daughter Katharine. Already susceptible to depression, her symptoms were exacerbated by marriage and motherhood. A good proportion of her diary entries from the time she gave birth to her daughter until several years subsequently draw the oncoming depression that she was to face.[37]

On April eighteen, 1887, Gilman wrote in her diary that she was very ill with "some brain disease" which brought suffering that cannot be felt past anybody else, to the point that her "listen has given way".[38] To begin, the patient could non even go out her bed, read, write, sew together, talk, or feed herself.[39]

After nine weeks, Gilman was sent domicile with Mitchell's instructions, "Live as domestic a life equally possible. Accept your child with yous all the fourth dimension... Lie down an hour after each meal. Take but 2 hours' intellectual life a day. And never touch pen, brush or pencil every bit long as yous live." She tried for a few months to follow Mitchell's communication, simply her depression deepened, and Gilman came perilously shut to a full emotional collapse.[twoscore] Her remaining sanity was on the line and she began to display suicidal behavior that involved talk of pistols and chloroform, as recorded in her husband's diaries. By early summertime the couple had decided that a divorce was necessary for her to regain sanity without affecting the lives of her husband and daughter.[14]

During the summer of 1888, Charlotte and Katharine spent time in Bristol, Rhode Island, away from Walter, and it was there where her depression began to lift. She writes of herself noticing positive changes in her attitude. She returned to Providence in September. She sold property that had been left to her in Connecticut, and went with a friend, Grace Channing, to Pasadena where the recovery of her low can be seen through the transformation of her intellectual life.[19]

Social views and theories [edit]

Reform Darwinism and the role of women in club [edit]

Gilman called herself a humanist and believed the domestic environment oppressed women through the patriarchal beliefs upheld by society.[41] Gilman embraced the theory of reform Darwinism and argued that Darwin'south theories of evolution presented only the male person as the given in the process of man development, thus overlooking the origins of the female brain in gild that rationally chose the best suited mate that they could find.

Gilman argued that male aggressiveness and maternal roles for women were artificial and no longer necessary for survival in mail-prehistoric times. She wrote, "In that location is no female listen. The brain is not an organ of sexual practice. Might as well speak of a female liver."[42]

Her principal argument was that sex activity and domestic economics went paw in mitt; for a adult female to survive, she was reliant on her sexual assets to please her husband and so that he would financially back up his family. From childhood, young girls are forced into a social constraint that prepares them for motherhood by the toys that are marketed to them and the dress designed for them. She argued that there should be no difference in the dress that niggling girls and boys wear, the toys they play with, or the activities they do, and described tomboys as perfect humans who ran around and used their bodies freely and healthily.[43]

Gilman argued that women's contributions to civilization, throughout history, have been halted because of an androcentric culture. She believed that womankind was the underdeveloped one-half of humanity, and improvement was necessary to prevent the deterioration of the human race.[44] Gilman believed economical independence is the only affair that could really bring freedom for women and make them equal to men. In 1898 she published Women and Economics, a theoretical treatise which argued, amidst other things, that women are subjugated by men, that motherhood should not preclude a adult female from working outside the home, and that housekeeping, cooking, and kid care, would exist professionalized.[45] "The ideal woman," Gilman wrote, "was not merely assigned a social role that locked her into her home, just she was also expected to like information technology, to be cheerful and gay, smiling and skilful-humored." When the sexual-economic relationship ceases to be, life on the domestic front would certainly improve, as frustration in relationships often stems from the lack of social contact that the domestic wife has with the outside globe.[46]

Gilman became a spokesperson on topics such as women'due south perspectives on work, wearing apparel reform, and family. Housework, she argued, should be every bit shared by men and women, and that at an early on age women should be encouraged to be independent. In many of her major works, including "The Dwelling house" (1903), Human Work (1904), and The Human-Made World (1911), Gilman too advocated women working outside of the home.[47]

Gilman argued that the domicile should exist socially redefined. The abode should shift from existence an "economic entity" where a married couple live together because of the economic benefit or necessity, to a place where groups of men and groups of women can share in a "peaceful and permanent expression of personal life."[48]

Gilman believed having a comfy and healthy lifestyle should not be restricted to married couples; all humans demand a home that provides these amenities. She suggested that a communal type of housing open to both males and females, consisting of rooms, rooms of suites and houses, should be constructed. This would permit individuals to live singly and yet accept companionship and the comforts of a abode. Both males and females would be totally economically independent in these living arrangements allowing for marriage to occur without either the male or the female'southward economical status having to modify.

The structural arrangement of the home is also redefined by Gilman. She removes the kitchen from the home, leaving rooms to be bundled and extended in whatever form and freeing women from the provision of meals in the home. The abode would become a true personal expression of the individual living in it.

Ultimately the restructuring of the abode and manner of living will allow individuals, especially women, to become an "integral office of the social structure, in shut, straight, permanent connexion with the needs and uses of society." That would be a dramatic change for women, who generally considered themselves restricted by family life built upon their economic dependence on men.[49]

Feminism in stories and novellas [edit]

Gilman created a world in many of her stories with a feminist point of view. Two of her narratives, "What Diantha Did", and Herland, are expert examples of Gilman focusing her work on how women are not just stay-at-home mothers they are expected to exist; they are also people who accept dreams, who are able to travel and work merely as men practise, and whose goals include a society where women are just as important as men. The world-edifice that is executed by Gilman, as well every bit the characters in these 2 stories and others, embody the change that was needed in the early on 1900s in a mode that is now commonly seen as feminism.

Gilman uses world-edifice in Herland to demonstrate the equality that she longed to see. The women of Herland are the providers. This makes them appear to be the dominant sex, taking over the gender roles that are typically given to men. Elizabeth Keyser notes, "In Herland the supposedly superior sex activity becomes the inferior or disadvantaged ..."[50] In this society, Gilman makes it to where women are focused on having leadership within the community, fulfilling roles that are stereotypically seen as existence male roles, and running an entire community without the same attitudes that men have concerning their work and the customs. Yet, the attitude men carried concerning women were degrading, specially by progressive women, like Gilman. Using Herland, Gilman challenged this stereotype, and made the gild of Herland a type of paradise. Gilman uses this story to ostend the stereotypically devalued qualities of women are valuable, prove strength, and shatters traditional utopian structure for hereafter works.[51] Essentially, Gilman creates Herland's club to take women agree all the power, showing more equality in this world, alluding to changes she wanted to see in her lifetime.

Gilman's feministic approach differs from Herland in "What Diantha Did". Ane grapheme in this story, Diantha, breaks through the traditional expectation of women, showing Gilman's desires for what a woman would be able to do in real-life society. Throughout the story, Gilman portrays Diantha as a graphic symbol who strikes through the paradigm of businesses in the U.Due south., who challenges gender norms and roles, and who believed that women could provide the solution to the corruption in big business in guild.[52] Gilman chooses to accept Diantha cull a career that is stereotypically not one a woman would have because in doing so, she is showing that the salaries and wages of traditional women'south jobs are unfair. Diantha's choice to run a business allows her to come up out of the shadows and join society. Gilman's works, peculiarly her work with "What Diantha Did", are a call for alter, a boxing cry that would cause panic in men and ability in women.[53] Gilman used her work as a platform for a call to change, as a way to reach women and have them brainstorm the motility toward freedom.

Race [edit]

In 1908, Gilman wrote an commodity in the American Journal of Folklore advocating hatred of African Americans and the reestablishment of slavery in America. Calling Black Americans "a large body of aliens" whose skin color made them "widely dissimilar and in many respects inferior," Gilman claimed non-whites' presence in America was "to us a social injury."[54] She proposed that all Blacks beneath "a certain grade of citizenship"—those who she decided were not "decent, self-supporting, [and] progressive...should exist taken hold of by the state."[54] Gilman advocated the enforced labor of Black "men, women and children," believed these laborers should not be paid until the cost of her labor plan was met, and used the term "enlistment" rather than "enslavement."[54]

Gilman'south racism lead her to espouse eugenicist beliefs, claiming Americans of onetime stock British descent were surrendering their country to immigrants who were diluting the nation's racial purity.[55] When asked about her stance on the matter during a trip to London she declared "I am an Anglo-Saxon before everything."[56] In an endeavour to gain the vote for all women, she spoke out against literacy voting tests at the 1903 National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in New Orleans.[57]

Literary critic Susan South. Lanser says "The Yellow Wallpaper" should exist interpreted by focusing on Gilman's racism.[58] Other literary critics have built on Lanser's work to understand Gilman'south ideas in relation to turn-of-the-century culture more broadly.[59] [lx]

Animals [edit]

Gilman'due south feminist works often included stances and arguments for reforming the use of domesticated animals.[61] In Herland, Gilman'due south utopian lodge excludes all domesticated animals, including livestock. Additionally, in Moving the Mount Gilman addresses the ills of animal domestication related to inbreeding. In "When I Was a Witch", the narrator witnesses and intervenes in instances of fauna use as she travels through New York, liberating work horses, cats, and lapdogs by rendering them "comfortably dead". One literary scholar connected the regression of the female narrator in "The Xanthous Wallpaper" to the parallel status of domesticated felines.[62] She wrote in a letter to the Saturday Evening Mail service that the automobile would eliminate the cruelty to horses used to pull carriages and cars.[63]

Critical reception [edit]

"The Yellow Wallpaper" was initially met with a mixed reception. One anonymous letter submitted to the Boston Transcript read, "The story could hardly, it would seem, give pleasure to any reader, and to many whose lives have been touched through the dearest ties by this dread disease, it must bring the keenest pain. To others, whose lives have become a struggle against heredity of mental derangement, such literature contains deadly peril. Should such stories be immune to pass without severest censure?"[64]

Positive reviewers describe it equally impressive because it is the most suggestive and graphic business relationship of why women who live monotonous lives are susceptible to mental disease.[65]

Although Gilman had gained international fame with the publication of Women and Economics in 1898, by the finish of World State of war I, she seemed out of tune with her times. In her autobiography she admitted that "unfortunately my views on the sex question do non entreatment to the Freudian complex of today, nor are people satisfied with a presentation of faith as a help in our tremendous work of improving this world."[66]

Ann J. Lane writes in Herland and Beyond that "Gilman offered perspectives on major bug of gender with which we still grapple; the origins of women's subjugation, the struggle to achieve both autonomy and intimacy in human relationships; the central role of work as a definition of self; new strategies for rearing and educating time to come generations to create a humane and nurturing environment."[67]

Bibliography [edit]

Gilman's works include:[68]

Poetry collections [edit]

- In This Our World,1st ed. Oakland: McCombs & Vaughn, 1893. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1895. second ed.; San Francisco: Press of James H. Barry, 1895.

- Suffrage Songs and Verses. New York: Charlton Co., 1911. Microfilm. New Haven: Enquiry Publications, 1977, History of Women #6558.

- The Subsequently Poesy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Newark, DE: Academy of Delaware Printing, 1996.

Short stories [edit]

Gilman published 186 short stories in magazines, newspapers, and many were published in her cocky-published monthly, The Forerunner. Many literary critics have ignored these short stories.[69]

- "Circumstances Alter Cases." Kate Field's Washington, July 23, 1890: 55–56. "The Xanthous Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 1995. 32–38.

- "That Rare Gem." Women'southward Periodical, May 17, 1890: 158. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 20–24.

- "The Unexpected." Kate Field's Washington, May 21, 1890: 335–half dozen. "The Yellowish Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 25–31.

- "An Extinct Angel." Kate Field's Washington, September 23, 1891:199–200. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 48–50.

- "The Giant Wistaria." New England Mag 4 (1891): 480–85. "The Xanthous Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 39–47.

- "The Yellow Wall-paper." New England Magazine 5 (1892): 647–56; Boston: Pocket-size, Maynard & Co., 1899; NY: Feminist Press, 1973 Afterword Elaine Hedges; Oxford: Oxford Upwardly, 1995. Introduction Robert Shulman.

- "The Rocking-Chair." Worthington's Illustrated i (1893): 453–59. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 51–61.

- "An Elopement." San Francisco Call, July x, 1893: ane. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upwardly, 1995. 66–68.

- "Deserted." San Francisco Call July 17, 1893: 1–2. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upwards, 1995. 62–65.

- "Through This." Kate Field's Washington, September 13, 1893: 166. "The Xanthous Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 69–72.

- "A Day's Berryin.'" Impress, October 13, 1894: 4–5. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995. 78–82.

- "Five Girls." Impress, December one, 1894: five. "The Yellowish Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 1995. 83–86.

- "1 Fashion Out." Impress, December 29, 1894: 4–5. "The Yellowish Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 87–91.

- "The Misleading of Pendleton Oaks." Impress, October 6, 1894: 4–five. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995. 73–77.

- "An Unnatural Mother." Print, February sixteen, 1895: 4–5. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 98–106.

- "An Unpatented Process." Impress, January 12, 1895: 4–5. "The Yellowish Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995. 92–97.

- "Co-ordinate to Solomon." Precursor 1:2 (1909):1–5. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 122–129.

- "Three Thanksgivings." Forerunner 1 (1909): 5–12. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 1995. 107–121.

- "What Diantha Did. A NOVEL". Forerunner 1 (1909–eleven); NY: Charlton Co., 1910; London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912.

- "The Cottagette." Forerunner 1:10 (1910): 1–five. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 130–138.

- "When I Was a Witch." Forerunner 1 (1910): 1–6. The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader. Ed. Ann J. Lane. NY: Pantheon, 1980. 21–31.

- "In Two Houses." Forerunner 2:seven (1911): 171–77. "The Xanthous Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 1995. 159–171.

- "Making a Change." Forerunner 2:12 (1911): 311–315. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upwardly, 1995. 182–190.

- "Moving the Mountain." Precursor 2 (1911); NY: Charlton Co., 1911; The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader. Ed. Ann J. Lane. NY: Pantheon, 1980. 178–188.

- "The Crux.A NOVEL." Forerunner 2 (1910); NY: Charlton Co., 1911; The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader. Ed. Ann J. Lane. NY: Pantheon, 1980. 116–122.

- "The Jumping-off Identify." Forerunner two:4 (1911): 87–93. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 148–158.

- "The Widow's Might." Forerunner 2:1 (1911): iii–vii. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 139–147.

- "Turned." Precursor 2:9 (1911): 227–32. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 182–191.

- "Mrs. Elder'due south Thought." Forerunner 3:2 (1912): 29–32. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 191–199.

- "Their Business firm." Precursor 3:12 (1912): 309–14. "The Yellowish Wall-Paper" and Other Stories''. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upwardly, 1995. 200–209.

- "A Council of State of war." Precursor 4:8 (1913): 197–201. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 235–243.

- "Bee Wise." Forerunner 4:7 (1913): 169–173. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995. 226–234.

- "Her Beauty." Precursor 4:ii (1913): 29–33. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 210–217.

- "Mrs. Hines's Money." Forerunner four:4 (1913): 85–89. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 1995. 218–226.

- "A Partnership." Forerunner five:six (1914): 141–45. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 253–261.

- "Begnina Machiavelli. A NOVEL." Precursor 5 (1914); NY: Such and Such Publishing, 1998.

- "Fulfilment." Precursor 5:three (1914): 57–61. "The Xanthous Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Up, 1995.

- "If I Were a Man." Concrete Culture 32 (1914): 31–34. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 262–268.

- "Mr. Peebles'southward Heart." Forerunner 5:ix (1914): 225–29. "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 269–276.

- "Dr. Clair'southward Identify." Forerunner six:six (1915): 141–45. "The Xanthous Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 295–303.

- "Girls and State." Precursor 6:5 (1915): 113–117. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upward, 1995. 286–294.

- "Herland. A NOVEL. " Precursor 6 (1915); NY: Pantheon Books, 1979.

- "Mrs. Merrill'south Duties." Forerunner six:three (1915): 57–61. "The Yellowish Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 277–285.

- "A Surplus Woman." Precursor vii:5 (1916): 113–eighteen. "The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford Upwardly, 1995. 304–313.

- "Joan's Defender." Forerunner 7:six (1916): 141–45. '"The Yellow Wall-Paper" and Other Stories. Ed. Robert Shulman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. 314–322.

- "The Daughter in the Pink Lid." Forerunner 7 (1916): 39–46. The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader. Ed. Ann J. Lane. NY: Pantheon, 1980. 39–45.

- "With Her in Ourland: Sequel to Herland. A NOVEL." Forerunner 7 (1916); Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997.

Novels and novellas [edit]

- What Diantha Did. Precursor. 1909–10.

- The Crux. Forerunner. 1911.

- Moving the Mountain. Forerunner. 1911.

- Mag-Marjorie. Forerunner. 1912.

- Won Over Precursor. 1913.

- Benigna Machiavelli Forerunner. 1914.

- Herland. Forerunner. 1915.

- With Her in Ourland. Forerunner. 1916.

- Unpunished. Ed. Catherine J. Gilt and Denise D. Knight. New York: Feminist Press, 1997.

Drama/dialogues [edit]

The bulk of Gilman's dramas are inaccessible as they are only available from the originals. Some were printed/reprinted in Forerunner, however.

- "Dame Nature Interviewed on the Woman Question as It Looks to Her" Kate Field'south Washington (1890): 138–40.

- "The Twilight." Impress (November 10, 1894): 4–5.

- "Story Studies", Impress, November 17, 1894: 5.

- "The Story Guessers", Impress, November 24, 1894: 5.

- "Three Women." Precursor 2 (1911): 134.

- "Something to Vote For", Forerunner ii (1911) 143-53.

- "The Ceaseless Struggle of Sex: A Dramatic View." Kate Field's Washington. April 9, 1890, 239–xl.

Non-fiction [edit]

- Women and Economics: A Report of the Economic Relation Between Men and Women equally a Factor in Social Development. Boston: Pocket-sized, Maynard & Co., 1898.

Book-length [edit]

- His Religion and Hers: A Written report of the Organized religion of Our Fathers and the Work of Our Mothers. NY and London: Century Co., 1923; London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1924; Westport: Hyperion Printing, 1976.

- Gems of Art for the Home and Fireside. Providence: J. A. and R. A. Reid, 1888.

- Concerning Children. Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1900.

- The Home: Its Work and Influence. New York: McClure, Phillips, & Co., 1903.

- Human Piece of work. New York: McClure, Phillips, & Co., 1904.

- The Man-Made World; or, Our Androcentric Civilization. New York: Charton Co., 1911.

- Our Brains and What Ails Them. Serialized in Precursor. 1912.

- Social Ethics. Serialized in Forerunner. 1914.

- Our Irresolute Morality. Ed. Freda Kirchway. NY: Boni, 1930. 53–66.

Curt and series non-fiction [edit]

- "Why Women Do Not Reform Their Apparel." Woman'south Journal, October ix, 1886: 338.

- "A Protestation Confronting Petticoats." Woman'southward Journal, January viii, 1887: lx.

- "The Providence Ladies Gymnasium." Providence Journal 8 (1888): two.

- "How Much Must We Read?" Pacific Monthly 1 (1889): 43–44.

- "Altering Human Nature." California Nationalist, May x, 1890: 10.

- "Are Women Improve Than Men?" Pacific Monthly 3 (1891): 9–xi.

- "A Lady on the Cap and Apron Question." Wasp, June half-dozen, 1891: 3.

- "The Reactive Lies of Gallantry." Belford's ns 2 (1892): 205–eight.

- "The Vegetable Chinaman." Housekeeper's Weekly, June 24, 1893: three.

- "The Saloon and Its Annex." Stockton Mail iv (1893): 4.

- "The Business League for Women." Print 1 (1894): 2.

- "Official Study of Woman'due south Congress." Impress one (1894): 3.

- "John Smith and Armenia." Print, Jan 12, 1895: 2–3.

- "The American Government." Woman's Cavalcade, June six, 1896: three.

- "When Socialism Began." American Fabian 3 (1897): ane–2.

- "Causes and Uses of the Subjection of Women." Woman's Journal, December 24, 1898: 410.

- "The Automobile as a Reformer." Saturday Evening Post, June 3, 1899: 778.

- "Esthetic Dyspepsia." Sabbatum Evening Post, August 4, 1900: 12.

- "Ideals of Child Culture." Child Stude For Mothers and Teachers. Ed Margaret Sangster. Philadelphia: Booklovers Library, 1901. 93–101.

- "Should Wives Piece of work?" Success 5 (1902): 139.

- "Fortschritte der Frauen in Amerika." Neues Frauenleben ane:ane (1903): 2–5.

- "The Passing of the Home in Great American Cities." Cosmopolitan 38 (1904): 137–47.

- "The Dazzler of a Block." Independent, July xiv, 1904: 67–72.

- "The Home and the Hospital." Good Housekeeping xl (1905): ix.

- "Some Light on the [Single Woman's] 'Trouble.'" American Magazine 62 (1906): 4270428.

- "Social Darwinism." American Journal of Folklore 12 (1907): 713–14.

- "A Proffer on the Negro Problem." American Journal of Sociology 14 (1908): 78–85.

- "How Home Weather React Upon the Family unit." American Journal of Sociology xiv (1909): 592–605.

- "Children's Article of clothing." Harper'south Boutique 44 (1910): 24.

- "On Dogs." Forerunner 2 (1911): 206–nine.

- "How to Lighten the Labor of Women." McCall's twoscore (1912): 14–15, 77.

- "What 'Love' Really Is." Pictorial Review 14 (1913): 11, 57.

- "Mucilage Chewing in Public." New York Times, May 20, 1914:12:v.

- "A Rational Position on Suffrage/At the Request of the New York Times, Mrs. Gilman Presents the Best Arguments Possible in Behalf of Votes for Women." New York Times Mag, March 7, 1915: xiv–15.

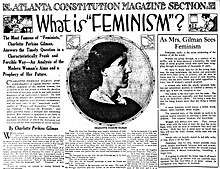

- "What is Feminism?" Boston Sunday Herald Magazine, September iii, 1916: 7.

- "The Housekeeper and the Food Problem." Annals of the American Academy 74 (1917): 123–xl.

- "Apropos Clothes." Independent, June 22, 1918: 478, 483.

- "The Socializing of Education." Public, April 5, 1919: 348–49.

- "A Adult female's Party." Suffragist 8 (1920): 8–9.

- "Making Towns Fit to Live In." Century 102 (1921): 361–366.

- "Cross-Examining Santa Claus." Century 105 (1922): 169–174.

- "Is America Besides Hospitable?" Forum lxx (1923): 1983–89.

- "Toward Monogamy." Nation, June 11, 1924: 671–73.

- "The Nobler Male." Forum 74 (1925): 19–21.

- "American Radicals." New York Jewish Daily Forwards 1 (1926): one.

- "Progress through Birth Control." North American Review 224 (1927): 622–29.

- "Divorce and Nascence Command." Outlook, January 25, 1928: 130–31.

- "Feminism and Social Progress." Problems of Civilization. Ed. Baker Brownell. NY: D. Van Nostrand, 1929. 115–42.

- "Sexual practice and Race Progress." Sex in Civilization. Eds V. F. Calverton and South. D. Schmalhausen. NY: Macaulay, 1929. 109–23.

- "Parasitism and Civilized Vice." Woman'south Coming of Age. Ed. S. D. Schmalhausen. NY: Liveright, 1931. 110–26.

- "Birth Control, Religion and the Unfit." Nation, January 27, 1932: 108–109.

- "The Right to Die." Forum 94 (1935): 297–300.

Self-publications [edit]

The Forerunner. Seven volumes, 1909–16. Microfiche. NY: Greenwood, 1968.

Selected lectures [edit]

There are 90 reports of the lectures that Gilman gave in The United States and Europe.[69]

- "Social club News." Weekly Nationalist, June 21, 1890: half dozen. [Re. "On Human being Nature."]

- "With Women Who Write." San Francisco Examiner, March 1891, 3:3. [Re. "The Coming Adult female."]

- "Safeguards Suggested for Social Evils." San Francisco Phone call, April 24, 1892: 12:4.

- "The Labor Motion." Alameda Canton Federation of Trades, 1893. Alameda County, CA Labor Union Meetings. September two, 1892.

- "Announcement." Impress one (1894): 2. [Re. Series of "Talks on Social Questions."]

- "All the Comforts of a Home." San Francisco Examiner, May 22, 1895: 9. [Re. "Simplicity and Decoration."]

- "The Washington Convention." Woman's Periodical, February 15, 1896: 49–l. [Re. California.]

- "Adult female Suffrage League." Boston Advertiser, November x, 1897: 8:one. [Re. "The Economic Basis of the Adult female Question."]

- "Bellamy Memorial Coming together." American Fabian 4: (1898): 3.

- "An Evening With Kipling." Daily Argus, March 14, 1899: 4:2.

- "Scientific Preparation of Domestic Servants." Women and Industrial Life, Vol. 6 of International Congress of Women of 1899. Ed Countess of Aberdeen. London: T. Unwin Fisher, 1900. 109.

- "Club and the Child." Brooklyn Eagle, December 11, 1902: 8:4.

- "Woman and Work/ Pop Fallacy that They are a Leisure Class, Says Mrs. Gilman." New York Tribune, February 26, 1903: 7:ane.

- "A New Light on the Woman Question." Woman's Journal, Apr 25, 1904: 76–77.

- "Straight Talk by Mrs. Gilman is Looked For." San Francisco Telephone call, July sixteen, 1905: 33:2.

- "Women and Social Service." Warren: National American Adult female Suffrage Association, 1907.

- "Higher Marriage Mrs. Gilman'southward Plea." New York Times, December 29, 1908: ii:iii.

- "Three Women Leaders in Hub." Boston Post, December 7, 1909: 1:ane–two and xiv:5–6.

- "Warless World When Women's Slavery Ends." San Francisco Examiner, November 14, 1910: 4:ane.

- "Lecture Given past Mrs. Gilman." San Francisco Call, November 15, 1911: seven:3. [Re. "The Social club-- Body and Soul."]

- "Mrs. Gilman Assorts Sins." New York Times, June 3, 1913: three:8

- "Adam the Real Rib, Mrs. Gilman Insists." New York Times, February 19, 1914: 9:3.

- "Advocates a 'World Urban center.'" New York Times, January 6, 1915: xv:5. [Re. Mediation of diplomatic disputes by an international bureau.]

- "The Listener." Boston Transcript, Apr xiv, 1917: fourteen:one. [Re. Proclamation of lecture serial.]

- "Great Duty for Women Later on War." Boston Mail service, February 26, 1918: ii:7.

- "Mrs. Gilman Urges Hired Mother Idea." New York Times, September 23, 1919: 36:1–2.

- "Eulogize Susan B. Anthony." New York Times, February 16, 1920: xv:vi. [Re. Gilman and others eulogize Anthony on the centenary of her nascency.]

- "Walt Whitman Dinner." New York Times, June ane, 1921: 16:seven. [Gilman speaks at annual meeting of Whitman Society in New York.]

- "Fiction of America Beingness Melting Pot Unmasked by CPG." Dallas Morning News, February 15, 1926: 9:7–8 and 15:eight.

Diaries, journals, biographies, and letters [edit]

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Making of a Radical Feminist. Mary A. Hill. Philadelphia: Temple Academy Press, 1980.

- A Journey from Inside: The Love Letters of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1897–1900. Ed. Mary A. Loma. Lewisburg: Bucknill UP, 1995.

- The Diaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 2 Vols. Ed. Denise D. Knight. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994.

Autobiography [edit]

- The Living of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: An Autobiography. New York and London: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1935; NY: Arno Press, 1972; and Harper & Row, 1975.

Academic studies [edit]

- Allen, Judith (2009). The Feminism of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Sexualities, Histories, Progressivism, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-01463-0

- Allen, Polly Wynn (1988). Edifice Domestic Liberty: Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Architectural Feminism, Academy of Massachusetts Printing, ISBN 0-87023-627-X

- Berman, Jeffrey. "The Unrestful Cure: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and 'The Yellow Wallpaper.'" In The Convict Imagination: A Casebook on The Yellow Wallpaper, edited by Catherine Golden. New York: Feminist Press, 1992, pp. 211–41.

- Carter-Sanborn, Kristin. "Restraining Lodge: The Imperialist Anti-Violence of Charlotte Perkins Gilman." Arizona Quarterly 56.2 (Summer 2000): 1–36.

- Ceplair, Larry, ed. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Nonfiction Reader. New York: Columbia Upwardly, 1991.

- Davis, Cynthia J. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography (Stanford University Printing; 2010) 568 pages; major scholarly biography

- Davis, Cynthia J. and Denise D. Knight. Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Her Contemporaries: Literary and Intellectual Contexts. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Printing, 2004.

- Deegan, Mary Jo. "Introduction." With Her in Ourland: Sequel to Herland. Eds. Mary Jo Deegan and Michael R. Hill. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997. 1–57.

- Eldredge, Charles C. Charles Walter Stetson, Color, and Fantasy. Lawrence: Spencer Museum of Art, The U of Kansas, 1982.

- Ganobcsik-Williams, Lisa. "The Intellectualism of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Evolutionary Perspectives on Race, Ethnicity, and Gender." Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Optimist Reformer. Eds. Jill Rudd and Val Gough. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1999.

- Gilt, Catherine. The Captive Imagination: A Casebook on The Xanthous Wallpaper. New York: Feminist Printing, 1992.

- ---. "`Written to Drive Nails With': Recalling the Early on Verse of Charlotte Perkins Gilman." in Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Optimist Reformer. Eds. Jill Rudd and Val Gough. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1999. 243-66.

- Gough, Val. "`In the Twinkling of an Middle': Gilman'south Utopian Imagination." in A Very Different Story: Studies on the Fiction of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Eds. Val Gough and Jill Rudd. Liverpool: Liverpool Upwards, 1998. 129–43.

- Gubar, Susan. "She in Herland: Feminism as Fantasy." in Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Woman and Her Piece of work. Ed. Sheryl L. Meyering. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989. 191–201.

- Hill, Mary Armfield. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Journey From Within." in A Very Unlike Story: Studies on the Fiction of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Eds. Val Gough and Jill Rudd. Liverpool: Liverpool UP, 1998. viii–23.

- Colina, Mary A. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Making of a Radical Feminist. (Temple Academy Printing, 1980).

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz, Wild Unrest: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Making of "The Xanthous Wall-Paper" (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Huber, Hannah, "Charlotte Perkins Gilman." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 381: Writers on Women'due south Rights and Us Suffrage, edited by George P. Anderson. Gale, pp. 140–52.

- Huber, Hannah, "'The Ane End to Which Her Whole Organism Tended': Social Evolution in Edith Wharton and Charlotte Perkins Gilman." Disquisitional Insights: Edith Wharton, edited by Myrto Drizou, Salem Printing, pp. 48–62.

- Karpinski, Joanne B., "The Economic Conundrum in the Lifewriting of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. in The Mixed Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Ed. Catherine J. Aureate and Joanne Southward. Zangrando. U of Delaware P, 2000. 35–46.

- Kessler, Ballad Farley. "Dreaming Ever of Lovely Things Beyond': Living Toward Herland, Experiential foregrounding." in The Mixed Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Eds. Catherine J. Gold and Joanna Schneider Zangrando. Newark: U of Delaware P, 2000. 89–103.

- Knight, Denise D. Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Study of the Brusque Fiction, Twayne Studies in Brusque Fiction (Twayne Publishers, 1997).

- ---. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Shadow of Racism." American Literary Realism, vol. 32, no. 2, 2000, pp. 159–169. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27746975.

- ---. "Introduction." Herland, `The Xanthous Wall-Newspaper' and Selected Writings. New York: Penguin, 1999.

- Lane, Ann J. "Gilman, Charlotte Perkins"; American National Biography Online, 2000.

- ---. "The Fictional Globe of Charlotte Perkins Gilman." in The Charlotte Perkins Gilman Reader. Ed. Ann J. Lane. New York: Pantheon, 1980.

- ---. "Introduction." Herland: A Lost Feminist Utopian Novel by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. 1915. Rpt. New York: Pantheon Books, 1979

- ---. To Herland and Beyond: The Life of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. New York: Pantheon, 1990.

- Lanser, Susan S. "Feminist Criticism, 'The Yellow Wallpaper,' and the Politics of Colour in America." Feminist Studies, Vol. 15, No. iii, Feminist Reinterpretations/Reinterpretations of Feminism (Autumn, 1989), pp. 415–441. JSTOR, Reprinted in "The Xanthous Wallpaper": Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Eds. Thomas L. Erskine and Connie Fifty. Richards. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1993. 225–256.

- Long, Lisa A. "Herland and the Gender of Science." in MLA Approaches to Pedagogy Gilman's The Xanthous Wall-Paper and Herland. Eds. Denise D. Knight and Cynthia J. David. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2003. 125–132.

- Mitchell, Due south. Weir, M.D. "Camp Cure." Nurse and Patient, and Army camp Cure. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1877

- ---. Article of clothing and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked. 1887. New York: Arno Printing, 1973.

- Oliver, Lawrence J. "W. E. B. Du Bois, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and 'A Suggestion on the Negro Trouble.'" American Literary Realism, vol. 48, no. 1, 2015, pp. 25–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/amerlitereal.48.1.0025.

- Oliver, Lawrence J. and Gary Scharnhorst. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman five. Ambrose Bierce: The Literary Politics of Gender in Fin-de-Siècle California." Journal of the West (July 1993): 52–60.

- Palmeri, Ann. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Precursor of a Feminist Social Science." in Discovering Reality: Feminist Perspectives on Epistemology, Metaphysics, Methodology and Philosophy of Science. Eds. Sandra Harding and Merrill B. Hintikka. Dordrecht: Reidel, 1983. 97–120.

- Scharnhorst, Gary. Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Boston: Twayne, 1985. Studies Gilman every bit author

- Scharnhorst, Gary, and Denise D. Knight. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman'south Library: A Reconstruction." Resources for American Literary Studies 23:2 (1997): 181–219.

- Stetson, Charles Walter. Endure: The Diaries of Charles Walter Stetson. Ed. Mary A. Hill. Philadelphia: Temple Upwardly, 1985.

- Tuttle, Jennifer S. "Rewriting the West Cure: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Owen Wister, and the Sexual Politics of Neurasthenia." The Mixed Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Eds. Catherine J. Golden and Joanna Schneider Zangrando. Newark: U of Delaware P, 2000. 103–121.

- Wegener, Frederick. "What a Comfort a Woman Md Is!' Medical Women in the Life and Writing of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. In Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Optimist Reformer. Eds. Jill Rudd & Val Gough. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1999. 45–73.

- Weinbaum, Alys Eve. "Writing Feminist Genealogy: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Racial Nationalism, and the Reproduction of Maternalist Feminism." Feminist Studies 27 (Summer 2001): 271–30.

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Charlotte Perkins Gilman". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved Baronial 21, 2018.

- ^ National Women's Hall of Fame, Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- ^ Gilman, Living, 10.

- ^ Denise D. Knight, The Diaries of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia: 1994) xiv.

- ^ Polly Wynn Allen, Building Domestic Liberty, (1988) 30.

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography., 26.

- ^ Gilman, "Autobiography", Affiliate 5

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography, 29.

- ^ a b Kate Bolick, "The Equivocal Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman", (2019).

- ^ "Charlotte Perkins Gilman: The Lost Messages to Martha Luther Lane" (PDF). betweenthecovers.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February xiii, 2020.

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography, 82.

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography, 90.

- ^ "Channing, Grace Ellery, 1862–1937. Papers of Grace Ellery Channing, 1806–1973: A Finding Aid". Harvard University Library . Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Knight, Diaries, 408.

- ^ Davis, Cynthia (December 2005). "Love and Economics: Charlotte Perkins Gilman on "The Woman Question"" (PDF). ATQ (The American Transcendental Quarterly). xix (4): 242–248. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Harrison, Pat (July iii, 2013). "The Evolution of Charlotte Perkins Gilman". Radcliffe Magazine. Harvard University. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 525.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 163.

- ^ a b Knight, Diaries.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 648–666.

- ^ a b c Knight, Diaries, p. 813.

- ^ Polly Wynn Allen, Building Domestic Liberty, 54.

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography 187, 198.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 409.

- ^ Gale, Cengage Learning (2016). A Study Guide for Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "Herland". p. Introduction five. ISBN9781410348029.

- ^ "The Yellow Wall-paper". The Feminist Press . Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ^ Julie Bates Dock, Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and the History of Its Publication and Reception. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1998; p. 6.

- ^ "Charlotte Perkins Gilman".

- ^ Dock, Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wall-Newspaper" and the History of Its Publication and Reception, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 601

- ^ Charlotte Perkins Gilman, "Women and Economics" in Alice S. Rossi, ed., The Feminist Papers: From Adams to de Beauvoir (1997), section 1 just, 572–576.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 681.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 811.

- ^ Sari Edelstein, "Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Yellow Paper". Legacy, 24(one), 72–92. Retrieved October 28, 2008, from GenderWatch (GW) database. (Document ID: 1298797291).

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 812.

- ^ Allen, Building Domestic Freedom, 30.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 323–385.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 385.

- ^ Knight, Diaries, 407.

- ^ Gilman, Autobiography, 96.

- ^ Ann J. Lane, To Herland and Beyond, 230.

- ^ Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Women and Economics (Boston, MA: Small, Maynard & Co., 1898).

- ^ Carl N. Degler, "Charlotte Perkins Gilman on the Theory and Practice of Feminism", American Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. ane (Spring, 1956), 26.

- ^ Davis and Knight, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Her Contemporaries, 206.

- ^ Gilman, Women and Economics.

- ^ Degler, "Theory and Practice," 27.

- ^ Degler, "Theory and Practice," 27–35.

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (2005). Kolmar & Bartkowski (eds.). Feminist Theory . Boston: McGrawHill. p. 114. ISBN9780072826722.

- ^ Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (2005). Kolmar & Bartkowski (eds.). Feminist Theory . Boston: McGrawHill. pp. 110–114. ISBN9780072826722.

- ^ Keyser, Elizabeth (1992). Looking Astern: From Herland to Gulliver's Travels. 1000.One thousand. Hall & Company. p. 160.

- ^ Donaldson, Laura E. (March 1989). "The Eve of De-Struction: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Feminist Recreation of Paradise". Women's Studies. xvi (3/iv): 378. doi:x.1080/00497878.1989.9978776.

- ^ Fama, Katherine A. (2017). "Domestic Data and Feminist Momentum: The Narrative Accounting of Helen Stuart Campbell and Charlotte Perkins Gilman". Studies in American Naturalism. 12 (ane): 319. doi:10.1353/san.2017.0006. S2CID 148635798.

- ^ Seitler, Dana (March 2003). "Unnatural Option: Mothers, Eugenic Feminism, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman'southward Regeneration Narratives". American Quarterly. 55 (i): 63. doi:10.1353/aq.2003.0001. S2CID 143831741.

- ^ a b c Gilman, Charlotte Perkins (July 1909 – May 1909). "A Suggestion on the Negro Problem". The American Journal of Folklore. 14 . Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Afterwards her divorce from Stetson, she began lecturing on Nationalism. She was inspired from Edward Bellamy'southward utopian socialist romance Looking Backward. Alys Eve Weinbaum, "Writing Feminist Genealogy: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Racial Nationalism, and the Reproduction of Maternalist Feminism", Feminist Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer, 2001), pp. 271–302. Accessed November three, 2008.

- ^ Davis, C. (2010). Charlotte Perkins Gilman: A Biography. Stanford University Printing. ISBN9780804738897 . Retrieved November xv, 2014.

- ^ Allen, Edifice Domestic Liberty, 52.

- ^ Susan S. Lanser, "The Yellow Wallpaper," and the Politics of Color in America," Feminist Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3, Feminist Reinterpretations/Reinterpretations of Feminism (Autumn, 1989), pp. 415–441 Accessed March 5, 2019

- ^ Denise D. Knight, "Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Shadow of Racism," American Literary Realism, Vol. 32, No. two (Winter, 2000), pp. 159–169, accessed March ix, 2019.

- ^ Lawrence J. Oliver, "W. Due east. B. Du Bois, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and 'A Suggestion on the Negro Problem'," American Literary Realism, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Fall 2015), pp. 25–39, accessed March 5, 2019

- ^ McKenna, Erin (2012). "Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Women, Animals, and Oppression". In Hamington, Maurice; Bardwell-Jones, Celia (eds.). Gimmicky Feminist Pragmatism. New York: Routledge Publishing. ISBN978-0-203-12232-7.

- ^ Golden, Catherine (Fall 2007). "Marking Her Territory: Feline Behavior in "The Yellow Wall-Paper"". American Literary Realism. xl: 16–31. doi:x.1353/alr.2008.0017. S2CID 161505591.

- ^ Stetson, Charlotte Perkins (June iii, 1899). "The Automobile as Reformer". Sabbatum Evening Post. 171 (49): 778. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ K.D., "Perlious Stuff," Boston Evening Transcript, April 8, 1892, p.6, col.two. in Julie Bates Dock, Charlotte Perkins Gilman's "The Yellow Wallpaper" and the History of Its Publication and Reception, (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania Country Academy Printing, 1998) 103.

- ^ Henry B. Blackwell, "Literary Notices: The Yellow Wall Paper," The Woman'south Journal, June 17, 1899, p.187 in Julie Bates Dock, Charlote Perkins Gilman'south "The Yellow Wall-paper" and the History of Its Publication and Reception, (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania Country University Press, 1998) 107.

- ^ Gilman, Living, 184

- ^ Gold, Catherine J., and Joanna Zangrando. The Mixed Legacy of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. (Newark: University of Delaware P, 2000) 211.

- ^ The bibliographic information is accredited to the "Guide to Research Materials" section of Kim Well'southward website: Wells, Kim. Domestic Goddesses. August 23, 1999. Online. Internet. Accessed Oct 27, 2008. Archived August 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kim Wells, "Domestic Goddesses," Archived August 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Women Writers.net, August 23, 1999. world wide web.womenwriters.internet/

External links [edit]

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman Society

- Works past Charlotte Perkins Gilman in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works past Charlotte Perkins Gilman at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or near Charlotte Perkins Gilman at Internet Archive

- Works by Charlotte Perkins Gilman at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman at Library of Congress Authorities, with 107 catalog records

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- The Feminist Press

- Essays by Charlotte Perkins Gilman at Quotidiana.org

- "A Guide for Research Materials"

- "Charlotte Perkins Gilman: Domestic Goddess"

- Petri Liukkonen. "Charlotte Perkins Gilman". Books and Writers

- Suffrage Songs and Verses

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman Papers. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Plant, Harvard Academy.

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman Digital Collection. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Plant, Harvard University.

Audio files [edit]

- The Yellowish Wallpaper, Suspense, CBS radio, 1948

- two short radio episodes of Gilman's writing, "California Colors" and "Matriatism" from California Legacy Projection.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlotte_Perkins_Gilman

Enviar um comentário for "Art Gems for the Home and Fireside 1890 Antique Book Mrs Charles Walter Stetson Plain Grey Cover"